“We believe that the American workers employed in the American way are unbeatable”

– Thomas Watson, Jr. to Nikita Khrushchev (The Spokesman, September 22, 1959)

On September 21, 1959, Nikita Khrushchev toured an IBM plant in San Jose, California. In Nikita Khrushchev and the Creation of a Superpower, Nikita’s son Sergei remembered how his father wasn’t particularly impressed with the state-of-the-art computers. Nikita was, however, enthralled by the company cafeteria.

Then, and decades later when I was an IBM employee, there were no executive lunchrooms. Manufacturing operators, engineers — up to the plant manager broke bread together. The food was sold at cost and served by cafeteria workers, who were also company employees. Nikita noted that through the cafeteria’s design, “management was deliberatively trying to make a demonstration of democracy.”

Of course there was another thing management was trying to do: discourage unionization.

The Threat/Game Theory Union Wage Model

Back in the day, many of IBM’s peers and competitors were unionized. IBM didn’t want to go down that path. As I was to learn in my nine years of management, the company felt the best way to avoid unionization was to offer everything a union offered — and more. Hourly workers’ pay grids were set locally, to account for different geographical living standards, but always set above local union scale. Pension and health benefit plans were top shelf.

IBM management school taught managers about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to hammer home the importance of a living wage.

IBM wasn’t the only non-union shop to mimic union employers. When the cable television industry began, it knew their employees would be working alongside unionized telecom and power company employees. Before it was acquired by Time Warner, NewChannels (a division of Newhouse Broadcasting) paid better than union scale for precisely that reason.

This behavior is well documented in academic literature.

“The results suggest, inter alia, that an increase in the extent of unionization in an industry has substantial positive effects on the wages of nonunion as well as union workers.” – William Moore, Robert Newman and James Cunningham, “The Effect of the Extent of Unionism on Union and Nonunion Wages” in the Journal of Labor Research, Winter 1985, Vol. 6, Issue 1, p.21.

Like all institutions, unions can be inefficient. The power base can fight hard to preserve the status quo that put them there instead of striving for more meaningful change. That being said, I personally benefited from unions without ever being a union member. Sadly, I am something of a relic.

When unionization in an industry declines, so do the wage and benefit premiums for free riders. When IBM’s peers became less and less unionized, it no longer felt compelled to offer union-equivalent pay and benefits.

And when a minimum-wage company comes into town, look out below.

“Our research finds that Wal-Mart Store openings lead to the replacement of better paying jobs with jobs that pay less. Wal-Mart’s entry also drives wages down for workers in competing industry segments such as grocery stores.” – Arinjarit Dube, T. William Lester and Barry Eidlin, A Downward Push: The Impact of Wal-Mart Stores on Retail Wages and Benefits

Costco, a key competitor pays its employees roughly double what Wal-Mart pays. But as this article entitled The High Cost of Low Wages in the Harvard Business Review, you get what you pay for:

“In return for its generous wages and benefits, Costco gets one of the most loyal and productive workforces in all of retailing, and, probably not coincidentally, the lowest shrinkage (employee theft) figures in the industry.”

In 2012, Costco made roughly $10,000 profit per employee while Wal-Mart netted about $7,500 per employee.

But paying a good wage is a tried and true business model, as demonstrated by Henry Ford.

In 1914, Henry Ford raised the amount his workers could earn from roughly $2.25 per day to $5 per day — far above other employers. Years later he recounted:

“The payment of five dollars a day for an eight-hour day was one of the finest cost-cutting moves we ever made,”

“Cutting wages is the easiest and most slovenly way to [boost business performance], not to speak of its being an inhuman way. It is, in effect, throwing upon labour the incompetency of the managers of the business.”

One of my favorite passages from Henry Ford’s book, My Life And Work, speaks to the stewardship of business owners:

“[The manufacturer] is an instrument of society and he can serve society only as he manages his enterprises so as to turn over to the public an increasingly better product at an ever-decreasing price, and at the same time to pay all those who have a hand in his business an ever-increasing wage, based upon the work they do. In this way and in this way alone can a manufacturer or any one in business justify his existence.”

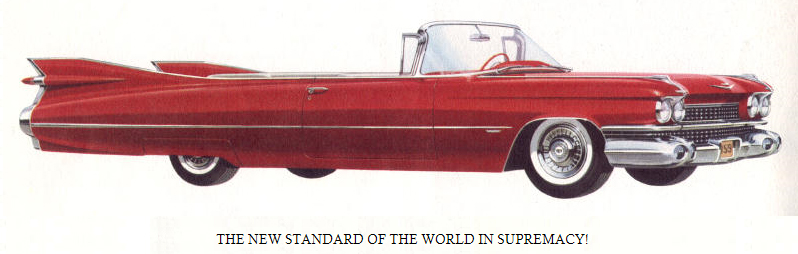

Although not documented anywhere that I could find, IBMers remember another thing Khrushchev was impressed with the day he toured the San Jose plant. He couldn’t believe that the workers owned the cars in the company parking lot. He thought the lot had been staged for his visit. Later that week, Nikita insisted on an unscheduled stop at a San Francisco grocery store. According to one account “The mere sight of the car-filled parking lot was enough for Khrushchev to admit that “we were ahead” of the USSR.”

In every respect, the financial stability of workers was “the American way” that Thomas Watson, Jr. professed — and Nikita Khrushchev coveted during the height of the Cold War.

Fun and Not-So-Fun Facts

In 1979, Thomas Watson Jr. was appointed the 16th United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union.

Thomas Watson Jr. was the principal benefactor of Brown University’s Watson Institute for International Studies. Sergei Khrushchev, who became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1999, still teaches there.

In 2012, 26.9% of fast food workers received food stamps. In the last ten years, the number of fast food employees grew 21.3%. The rest of the economy only added 3.2% more employees. In 2000, the average age of a fast food worker was 22. Today the average age of a fast food worker is 29.5.

JP Morgan’s contribution to House and Senate Agriculture Committees more than doubled once JP Morgan got into the food stamp business. JP Morgan is one of only three companies to administer EBT cards (the new food stamps), overseen by the Ag. Committees.(Profits from Poverty: How Food Stamps Benefit Corporations)

One Wal-Mart Supercenter in Wisconsin could cost taxpayers $904,542 a year if all the employees who qualified for food stamps, low cost housing and Medicaid applied.

In 2012, the CEO of Wal-Mart made a base salary of $1.3 million, received a $4.4 million bonus and $13.6 million in stock options.

In 2012, 284,000 college graduates worked in minimum wage jobs. (Number of the Week: College Grads in Minimum Wage Jobs)

IBM no longer offers pensions. The company only matches its 401(K) contribution once a year. If you get laid off on December 10th, you not only lose your job, you lose your 401(K) matching contributions for the year.

IBM’s first basic belief was “respect for the individual.” The only place you can find that now is on the company’s “history” subdirectory. It makes a great nostalgic Labor Day read. (IBM Management Principles and Practice)