In 1998 Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) lost $4.6 billion in less than four months. Although the hedge fund was led by Nobel Prize winners (Myron Scholes and Robert Merton), noted professors, a Federal Reserve vice chairman and well-known Wall Street arbitrage experts, it made one of the most basic — but costly — investment mistakes.

LTCM ran out of cash at the wrong time. The hedge fund’s managers got caught in one bad investment. To get themselves right again, they had to sell off sound investments. In the end, they turned one loss into many.

As investors, we’ve been made to believe that to maximize our returns we need to have every penny of our portfolio actively working for us. Either you’re fully invested or you’re a wuss. LTCM’s shortsightedness probably had more to do with greed, however, than courage. In its heyday, it had the chance to take on more investors and turned them down. After all, high leverage and a small number of investors had generated a fortune. When the shit hit the fan, LTCM couldn’t find the cash, and new investors were no where to be found. You can read about LTCM’s spectacular failure in two compelling books, When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management and Inventing Money: The Story of Long-Term Capital Management and the Legends Behind It

.

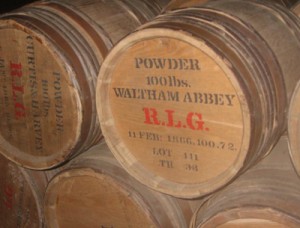

Powder Power

On October 19, 1987, the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 23%. Most hedge funds were crippled in the wake of “Black Monday,” but not Princeton/Newport Partners. Founded by mathematics professor Edward Thorp, the hedge fund did sustain some minor losses that day. But Princeton/Newport had enough dry powder to go in and by some distressed, but valuable, securities in the days that followed. In 1987, the S&P 500 managed to eke out a 5% gain. Thorpe’s hedge fund returned 27% that year.

Thorpe’s hedge funds and his personal portfolio have been profitable for 42 consecutive years. But Edward Thorp is probably more famous for his work outside of the investment world. In 1962, Thorp wrote Beat the Dealer: A Winning Strategy for the Game of Twenty-One (Vintage)

Thorpe’s hedge funds and his personal portfolio have been profitable for 42 consecutive years. But Edward Thorp is probably more famous for his work outside of the investment world. In 1962, Thorp wrote Beat the Dealer: A Winning Strategy for the Game of Twenty-One (Vintage). The book introduced the technique of card counting and revolutionized blackjack strategy. Decades later, it was used as a training manual for the famous MIT blackjack team.

While many people understand the playing strategy in Thorp’s book, few understand the significance of its betting strategy. Thorp used a strategy devised by the physicist John Kelly Jr. in 1956. The Kelly criterion is a mathematical system of betting whereby a player increases the size of their bets when the odds are in his or her favor. Bets are decreased when the odds of winning are lower. Using Kelly’s formula, there is NEVER a time when it is appropriate to have an entire bankroll in play — no matter how good the odds.

Thorp understood that to win at blackjack — and investing — you had to be able to withstand a losing streak. He didn’t want to be strapped for cash when the odds turn in his favor.

Selling into a Rally Isn’t Folly; It’s the Plan

In 2009, my company generously donated $100,000 to my Stock of the Month portfolio for me to manage. I don’t get monthly inflows like a 401(k) account and I don’t make annual contributions like an IRA account. And I sincerely doubt my company would give me more money if I were to lose what it has already given me. As a result, I tend to carry a larger cash balance than most.

That said, I’ve added to my cash balance throughout the rally of 2013. I believe in the wisdom of buying low and selling high. To achieve this, however, one actually has to sell. In April, I sold off half my Yahoo (YHOO) holdings for a 50.2% return. While I was comfortable that it had some run left, I was ready to take some off the table. I sold the balance at the end of July for a return of 78.8%.

My editor asked me if I regretted selling half of my position when I had. Was he shitting me? Hell, I’ll do a victory dance dedicated to that trade until my ashes are scattered. The day I regret beating the market by 39 percentage points is the last day I invest.

My editor asked me if I regretted selling half of my position when I had. Was he shitting me? Hell, I’ll do a victory dance dedicated to that trade until my ashes are scattered. The day I regret beating the market by 39 percentage points is the last day I invest.

If you’re an investor that cries every time you miss the tippy-top, you’re going to die of dehydration.

The “powers that be” have also been concerned about my recent trend of buying smaller positions — as I sold off larger positions. For me, this is my imperfect application of the Kelly criteria, I believe that the odds in the market are a bit weak and I want to be sure I have enough dry powder to take advantage of better odds in the near future.

Apparently, I am not alone. In a recent post on The Reformed Broker (a must-read blog for anyone who has a dime in the market), Josh Brown commented on a Bloomberg article that discussed the growing hoard of cash on the balance sheet of value managers.

I don’t consider myself a value investor per se. (Although if you’ve read #53 on the 50-Plus Things About Amy page, you know I hate to pay retail for anything) I’m only an OK blackjack player — certainly nothing like Edward Thorp. But I am a poker player and an investor. Those two activities have taught me to get my money in when the odds are in my favor. They’ve also taught me to take some money off the table when the odds are weak.

(For all my old PokerSchoolOnline buddies, you probably learned Bankroll 101 from the master, Debonair. His 2004 post “How I Never Go Broke” still lives. And after all these years, I can attest that Debonair is flush — and has still yet to go broke.)

2 Comments